Stop 10: “The Chateau”

The Demuth Museum | 120 East King Street

The double-width property at 118-120 East King Street was built in 1750 and was originally the “William Pitt, Earl of Chatham” Tavern.

William Pitt, Earl of Chatham Sign, Landis Valley Museum Collection

Demuth’s Great Grandfather Jacob, who had 20 children, purchased the building in 1836 to house his growing family. When Charles was born, his Great Aunt Louise was living in the house. When she passed in 1889, Demuth’s Father inherited the house. He had the first floor rooms of 118 & 120 converted to office space to provide additional income for the family, reserving a narrow hallway from the door at 118 to the dining room at the rear which included the staircase to the family’s rooms on the second floor. The offices were rented by John E. Snyder for his law practice.

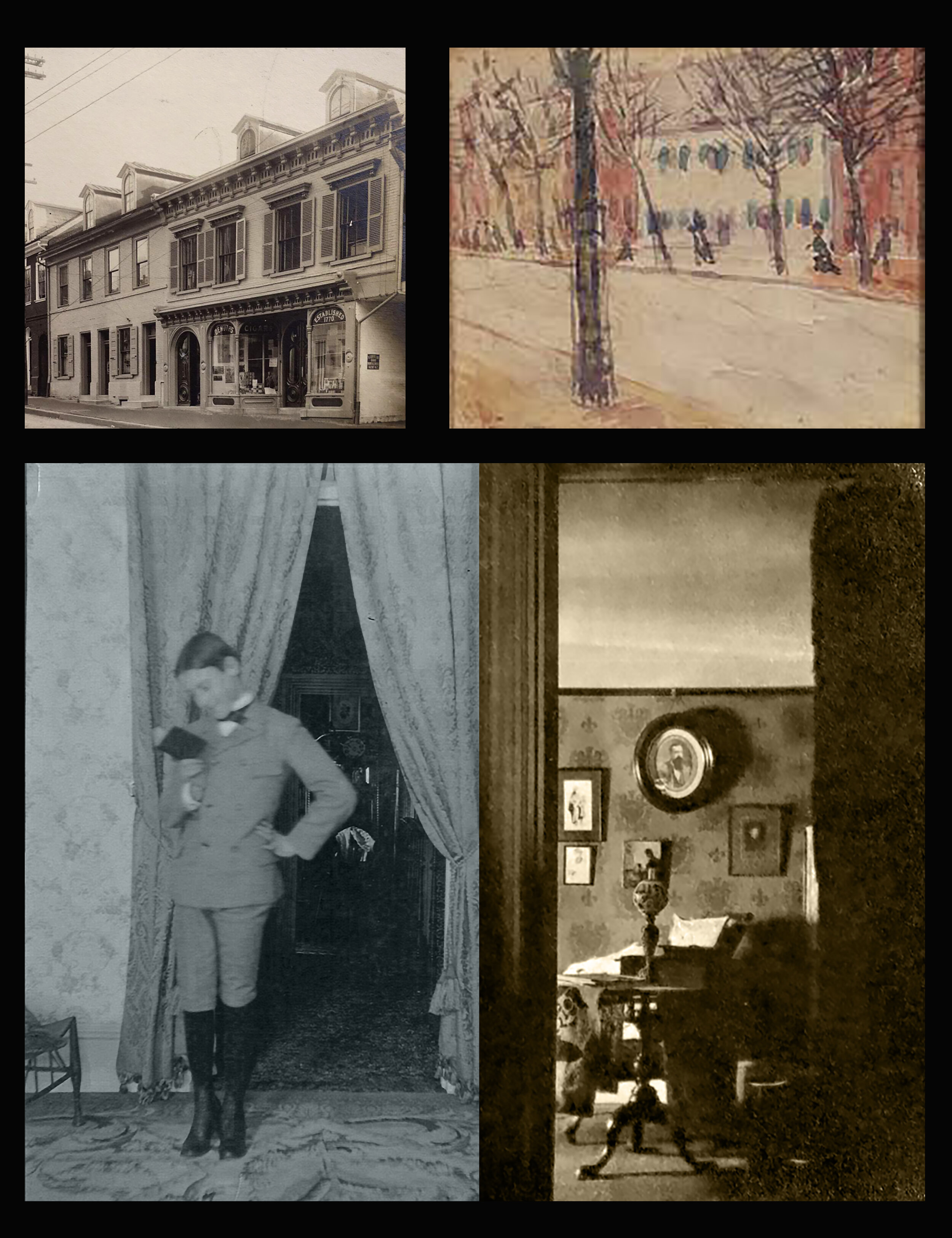

When Charles was growing up, the house was richly decorated in the Victorian style. Marsden Hartley claimed: “It belongs to the era of shell flowers, wax fruit, painted velvet, bead-encrusted antimacassars, and the usual complement of horsehair, bell pulls, opaque glass, silver lustre, and all the lavish profusion of accessory of such periods.”73

In 1917, Demuth and Robert Locher redecorated the house to give it a more modern sensibility without sacrificing its historical character. Henry McBride wrote to Florine Stettheimer in 1927: “The Demuth house is a knock-out, as you might guess. It’s in the heart of town, with a narrow entrance (decorated chastely by Bobby Locher) that opens out into bigger rooms at the back, which in turn look out on delightful gardens, in which there is a long brick terrace and many brick walks. The flowers are plentiful and many of them are family relics that have nothing to do with the fashions of the day…The house is full of quaint furniture and some amusing works of art. Among the latter are things by Marin, Louis Bouche, Pascin, and Georgia O’Keeffe. There are no Florine Stettheimers, which I thought odd. One would look well in my room, which is all in white, with a wallpaper of small dots at regular intervals. I told Charles he’d have to have you down here, but he smiled curiously and said he didn’t think you’d come.”74

The house was a source of pride and inspiration for Demuth, as well as a refuge. Hartley commented: “He spent, because he had a talent for decoration, much of his time making the quaint and typical brick house on King Street...into all but a de luxe affair inside. When he was at home, he liked it thoroughly, as when he was abroad he liked the usual variations of such character.”75

Now that we have had the chance to meet Charles and some of the people closest to him, we should take a moment and consider the impact of his life.

Marcel Duchamp called him “An artist worthy of the name, without the pettiness which afflicts most artists, worshiping his inner self without the usual eagerness to be right.”76 McBride wrote: “Elegance was an insistent aspiration with [Demuth]. He may be said to have translated Cubism “into American”, and to have added to it some of his native elegance. [The Demuth Retrospective] exhibition is a curious instance of what an artist can do with his public once he has gained a public, for Demuth practiced many devices that are not forgiven to all American painters. For instance, many persons who condemn cubism as the sin of all sins, have openly admired the several watercolor versions of Sir Christopher Wren church steeples without seeming to be aware that the drawings are cubistic. It is quite refined and delicate cubism, but it is cubism just the same.”77 His friend Darrell Larsen once asked him why, if he was so inspired by the Modern artists working in Paris at the turn of the century, his work didn’t look French? Demuth replied, “Perhaps it’s because I understand them.”78

Demuth certainly understood the modern techniques developed in Paris, Munich, Berlin, and Vienna, but he also understood the conservative nature of American collectors and the unique mythology of American culture. Growing up in Lancaster—one time Capitol of the United States and steeped in colonial history—Demuth was surrounded by reminders of America’s attempts to define itself as distinct from Europe: the architecture, the food, the music, and vaudeville. He used these to create a distinctly American style of art: Precisionism. He pioneered innovative techniques for watercolor that have become standard today, including salting and blotting to add texture to the image. If you look closely at the watercolor: ”Tree Forms” (1916), you can see the pattern of his lace handkerchief that he used to plot the green paint.

Demuth also created a visual vocabulary to express his homosexuality, the loneliness and isolation of modern life, and the sense of loss his generation felt for the “superior trifles”79 of the past. He strived and struggled to create art about America for Americans which possessed all the quality and innovation of Europe—and in doing so laid the foundation for American Art’s prominence in the 20th Century. He wrote to Alfred Stieglitz in 1928: “Europe was to us all nearer & dearer, but,--well, you know. What could any of us add to Europe? Perhaps I like to suffer. At times I think I do. It may never flower,--this our state, but if it does I should like to feel from some star, or whatever, that my living added a bit,--for in this flower, if it does, I can imagine Rome in its glory looking very mild.”80

The dominance of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, as well as New York City, in the second half of the 20th Century are due in part to the contributions of Charles Demuth and the other members of the Stieglitz Circle in the 1910s and 1920s. Artists like Georgia O’Keeffe, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Robert Indiana, and others have been inspired by Demuth’s paintings, and through them his influence ripples across American art to this day.

73 Hartley: “Farewell, Charles”. P.560

74 Kellner: Letters of Charles Demuth. P.97, ft1

75 Hartley, “Farewell, Charles”. P.560

76 Ritchie, Andrew Carnduff. Charles Demuth. The Museum of Modern Art: New York. 1950. P.17

77 McBride: The Flow of Art. P355-356

78 Farnham: Life, Psychology, & Works, Vol. 3. P.995

79 Hartley: “Farewell, Charles”. P.559

80 Kellner, Letters, p. 109