Stop 1: The Terrace

Demuth Museum | 120 East King Street

Welcome to the Demuth Museum audio tour of Demuth’s Lancaster. My name is David Shoemaker, and I will be your guide.

For today’s tour, we are going to follow the route Charles Demuth regularly took for his evening strolls.

According to his friend Darrell Larsen, he used to “walk down East King Street to the city square, then down Queen Street to the Brunswick Hotel where he would remain awhile and watch the people, returning the other way down Duke Street.” 1 Along this route, we will stop at 10 sites and discuss the people and events who helped shape his life and career.

In 1956, twenty years after Demuth’s death, Marcel Duchamp commented “Already, Demuth is a legend. Funny, how a man can disappear…” 2 I have spent the past 5 years trying to find the man behind the legend.

My favorite description of Demuth comes from a mostly negative review of a group art exhibition in New York, published in the Philadelphia Inquirer on Sunday, April 27th, 1919. The critic Helen Henderson wrote: “There are 125 pictures shown and among the exhibitors are several perfectly reputable painters. One can perhaps understand Charles Demuth, of Lancaster, associating himself with such ineptitudes because he is a whimsical person, fond of exotics, apt to try everything, and as one of his most loveable qualities quite devoid of pose in any sense." 3

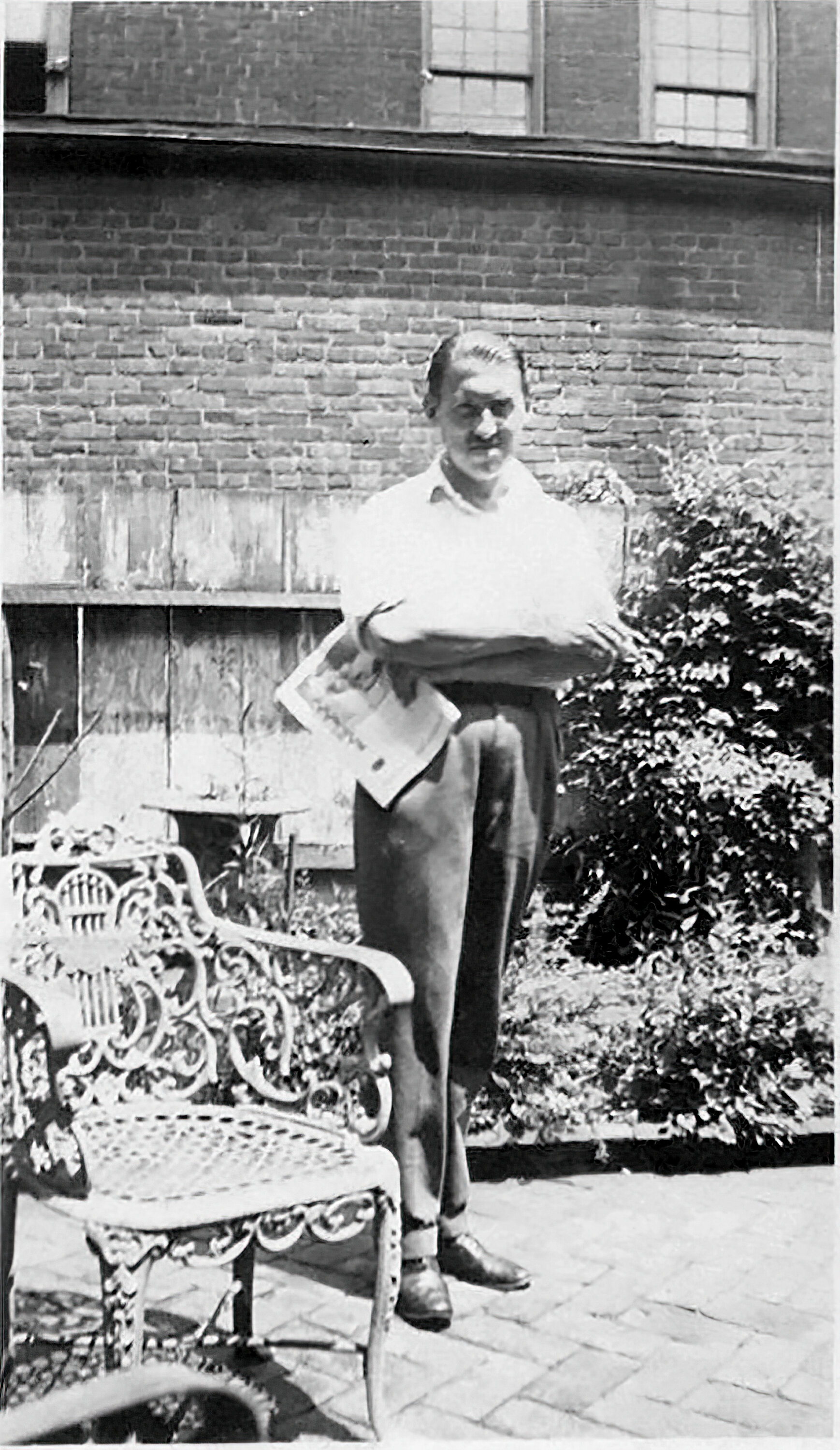

My favorite photographs of Demuth, which I think best capture his “great joy in living” 4 which made “him more fun than the other artists” 5 , were taken by the sculptor Arnold Rönnebeck in his Paris studio in 1913.

In them, we can see Demuth’s habit of sitting “crooked, sideways on the chair or sofa, with one shoulder much higher than the other, and with his neck strained into a funny position because of where his shoulders were.”6 His lower jaw stuck out; his ears stuck out. He had a lazy eye, which could make him appear cross-eyed at times.

Because of this, he rarely looked right at you; instead, he developed “an evasive way of looking aslant at the ground or up at the ceiling when addressing you, followed by short, intense looks of inquiry.”7 He joked about this in a letter to Georgia O’Keeffe when he wrote: “I did see your paintings. I looked at them carefully several times. I know that I never seem to look but I see pictures out of corners of my eyes.”8

“Charles dressed always in the right degree of good taste, English taste of course, carrying his cane elegantly and for service, not for show, as he always had need of a cane9…Because of a hip infirmity, he had invented a special sort of ambling walk which was so expressive of him.”10 Charles Daniel, owner of the Daniel Gallery, said: “Ah, Demuth. He was a rare one. I can tell you this right now—he wore the most beautiful neckties in New York. He must have the tie that he liked, and he liked the best. That was Demuth. It had to be good. He was very vain and wore unusual colors.”11

Sketch of Charles Demuth c. 1921 by Julius T. Bloch, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of the Executors of the Estate of Julius Bloch, 1967. 1967-109-7

Demuth with Cane: Demuth Museum Archives

Portrait of Charles Demuth by Alfred Stieglitz

New York Socialite Susan Watts Street said “Demuth was a terrific snob in a very kind sort of way. (Once when we were eating somewhere at a better restaurant Demuth made the remark: ‘Glad to get out of the paper napkin belt.’) 12 And he was meticulous, but not fussy. I remember that he liked to write notes in green ink on pink paper.” 13 Demuth had a high, squeaky voice with a very heavy Lancaster Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania German) accent and a high giggle that sounded like the whinny of a horse. 14 He would sometimes use Pennsylvania Dutch phrases like “Appearances must be kep up” and “Is your off off?” (It means “Has your vacation ended?”). 15 He frequently used the phrase “It’s the last word in that!” when complimenting friends’ clothing or accessories.

Demuth Letters: Richard W. C. Weyand collection of Charles Demuth. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Photo by David T. Shoemaker.

He had a stream of consciousness style of writing and developed his own punctuation, a comma followed by a dash, to indicate “pause, new thought”. You get a sense of it in the letter he sent to Gilbert Seldes on 13 November, 1922:

My Dear Seldes,

Please pardon me,-- I just forgot it, really I did, and I don’t understand it, as I’m as anxious as the best of “them” towards fame (so called) or publicity.

Here goes: I was born Nov 8th 1883, studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts under William M Chase and Thomas Anschutz. I went to Paris in 1907 for the first time and afterwards returned to it in 1912 and in 1921, living there and in London during these visits, about four years in all.

I have exhibited at the Penna. Academy and at the Daniel Gallery in New York City.

I think this is about the limit of my knowledge about myself. I suppose you will answer: “Know thyself, young man.”

Sincerely,

Demuth 16

The letter also displays Demuth’s characteristic modesty and self- deprecating wit. In 1933, Demuth sent a letter to Fiske Kimball, the Director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: “In answer to both your wire & letter concerning the meeting at the Museum regarding the needy artist, I don’t believe that Lancaster Co. has any artists, needy or otherwise. I’m afraid most of us are farmers,--I think I’m the only one probably in the county foolish enough to have gone in for so called art. However, if there is anything that I can do I would be glad to help.” 17 While Demuth was not actually a farmer, he did help his mother in the garden.

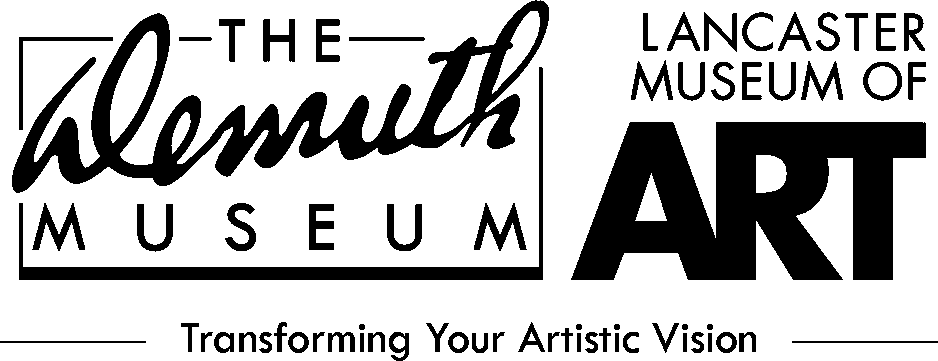

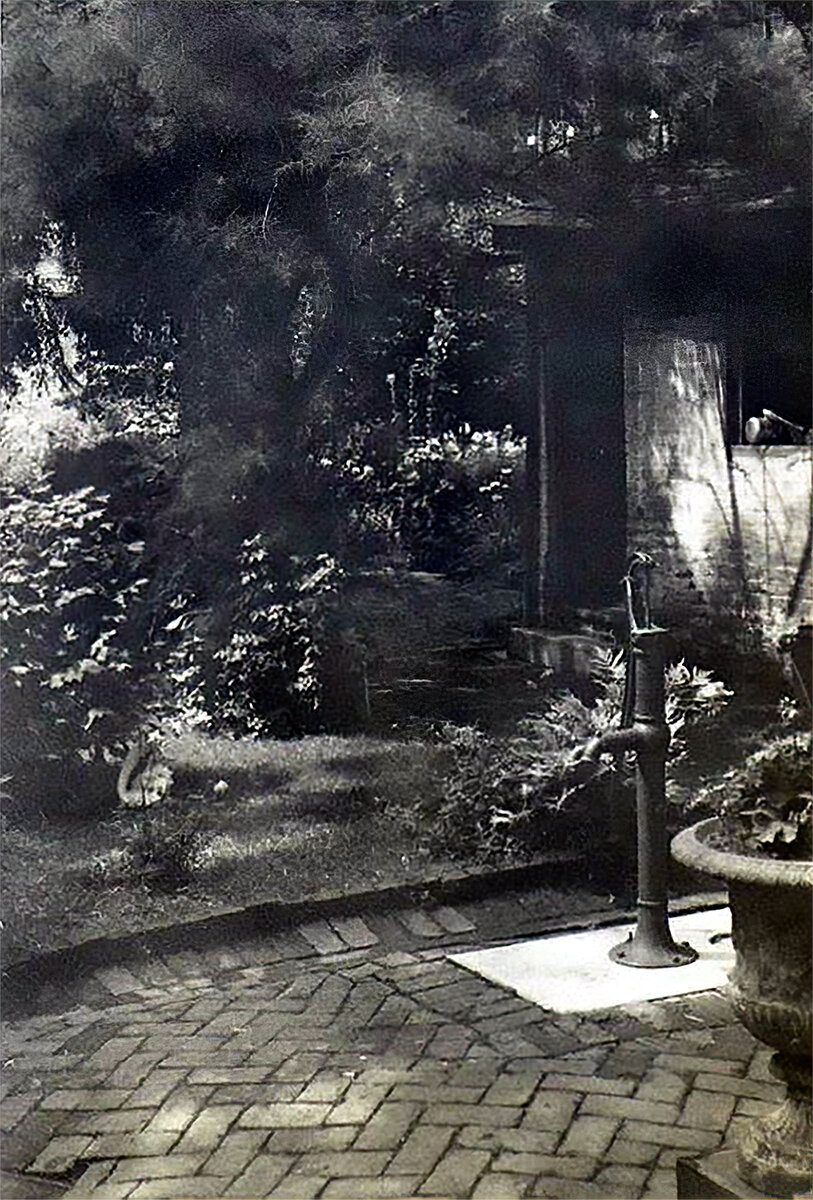

Originally, the garden extended all the way back to Mifflin Street. This brick paved terrace served as an outdoor sitting room where Charles would sometimes read the newspaper. Demuth’s friend, the art critic Henry McBride, wrote “The Demuth home is a knock-out, as you might guess…a narrow entrance opens out into bigger rooms at the back, which in turn look out on delightful gardens, in which there is a long brick terrace and many brick walks. The flowers are plentiful and many of them are family relics that have nothing to do with the fashions of the day. […] And there’s a marvelous church steeple to be seen from the garden—the finest I’ve seen in America.

Trinity Lutheran Church Steeple: Richard W. C. Weyand collection of Charles Demuth. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Photograph by Ferdinand A. Demuth.

More or less Baroque and foolish, but adorable. Square brick tower rises above the roof and the rest in white wood, with four large prophets at the four corners. The tower contains great bells, which raise a frightful din on Sunday morning at eight o’clock, but the congregational singing was charming from a distance of sixty feet. They wound up with ‘America’ so nicely, I almost wept.”18 This is the steeple of Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, where Charles was baptized and which his Mother Augusta regularly attended. In her will, she left $10,000.00 for the painting and upkeep of the steeple (and a memorial stained glass window for her parents and sisters). The design of the mariner’s star painted on the ceiling of the steeple is attributed to Demuth.

We will now head through the gate into the parking lot behind the museum to what was the south lawn portion of the gardens, to see the inspiration for two of Demuth’s Paintings.

1 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.994

2 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.973

3 “Philadelphia Inquirer, Sunday Morning, April 27th 1919”, Newspapers.com, p.76

4 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.994

5 Brubaker, “The Scribbler”, 12/18/1987

6 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.975

7 Williams, Autobiography, p.151

8 Kellner, Letters, p. 72

9 (Hartley, 1936) p.555

10 (Hartley, 1936) p554.

11 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.990-991

12 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.979

13 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.976

14 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.975

15 Watson & Morris, An Eye on the Modern Century, p. 170

16 Kellner, Letters, p. 43-44

17 Kellner, Letters, p.136

18 Kellner, Letters, p.97